Paper money

Paper money, often referred to as a note or a bill (North American English), is a type of negotiable promissory note that is payable to the bearer on demand, making it a form of currency. The main types of paper money are government notes, which are directly issued by political authorities, and banknotes issued by banks,[1] namely banks of issue including central banks. In some cases, paper money may be issued by other entities than governments or banks, for example merchants in pre-modern China and Japan.[citation needed] "Banknote" is often used synonymously for paper money, not least by collectors, but in a narrow sense banknotes are only the subset of paper money that is issued by banks.[2]

Paper money is often, but not always, legal tender, meaning that courts of law are required to recognize them as satisfactory payment of money debts.[3]

Counterfeiting, including the forgery of paper money, is an inherent challenge. It is countered by anticounterfeiting measures in the printing of paper money. Fighting the counterfeiting of notes (and, for banks of cheques) has been a principal driver of security printing methods development in recent centuries.

History

[edit]Code of Hammurabi Law 100 (c. 1755–1750 BC) stipulated repayment of a loan by a debtor to a creditor on a schedule with a maturity date specified in written contractual terms.[4][5][6] Law 122 stipulated that a depositor of gold, silver, or other chattel/movable property for safekeeping must present all articles and a signed contract of bailment to a notary before depositing the articles with a banker, and Law 123 stipulated that a banker was discharged of any liability from a contract of bailment if the notary denied the existence of the contract. Law 124 stipulated that a depositor with a notarized contract of bailment was entitled to redeem the entire value of their deposit, and Law 125 stipulated that a banker was liable for replacement of deposits stolen while in their possession.[7][8][6]

Carthage was purported to have issued government notes on parchment or leather before 146 BC. Hence Carthage may be the oldest user of lightweight promissory notes.[9][10][11] In China during the Han dynasty, promissory notes appeared in 118 BC and were made of leather.[12] Rome may have used a durable lightweight substance as promissory notes in 57 AD, which have been found in London.[13]

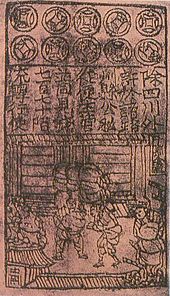

The first documented paper money was issued during the Tang dynasty and Song dynasty of China, starting in the 7th century, called "flying money".[14] Its roots were in merchant receipts of deposit during the Tang dynasty (618–907), as merchants and wholesalers desired to avoid the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions.[15][16][17] Although government issued centralized paper money did not appear until the 11th century, during the Song dynasty.

In Europe, cloth notes were in use in Prague in 960 and as part of the banking scheme of the Knights Templars around 1150.

The first European attempt by a bank of issue at issuing banknotes was in 1661 by Stockholms Banco, whose legacy was soon taken over by Sweden's Sveriges Riksbank.[18] The French Revolution resulted in the mass issuance of government notes known as assignats whose value soon collapsed, leading Napoleon to establish the Bank of France to issue paper banknotes in the early 1800s.[19]

Cash paper money originated as receipts for value held on account "value received", and should not be conflated with promissory "sight bills," which were issued with a promise to convert at a later date.

The perception of paper money as currency has evolved over time. Originally, money was based on precious metals, or commodity money. Paper money was seen by some as an I.O.U. or promissory note: a promise to pay someone in precious metal on presentation (see representative money). But they were readily accepted—for convenience and security—in London, for example, from the late 1600s onwards. With the gradual removal of precious metals from the monetary system, paper money evolved into pure fiat money.

Early Chinese paper money

[edit]

The first known paper money instrument was used in China in the 7th century, during the Tang dynasty (618–907). Merchants would issue what are today called promissory notes in the form of receipts of deposit to wholesalers to avoid using the heavy bulk of copper coinage in large commercial transactions.[15][16][17] Before these notes, circular coins with a rectangular hole in the middle were used. Multiple coins could be strung together on a rope. Merchants found that the strings were too heavy to carry around easily, especially for large transactions. To solve this problem, coins could be left with a trusted person, with the merchant being given a slip of paper (the receipt) recording how much money they had deposited with that person. Their coins would be restored when they went back and gave that person the paper.

True paper money, called "jiaozi", developed from these promissory notes by the 11th century, during the Song dynasty.[20][21] By 960, the Song government was short of copper for striking coins, and issued the first generally circulating notes. These notes were a promise by the ruler to redeem them later for some other object of value, usually specie. The issue of credit notes was often for a limited duration, and at some discount to the promised amount later. The jiaozi did not replace coins but was used alongside them.

The central government soon observed the economic advantages of printing paper money, issuing a monopoly for the issue of these certificates of deposit to several deposit shops.[15] By the early 12th century, the amount of notes issued in a single year amounted to an annual rate of 26 million strings of cash coins.[17] By the 1120s, the central government started to produce its own state-issued paper money (using woodblock printing).[15]

Even before this point, the Song government was amassing large amounts of paper tribute. It was recorded that each year before 1101, the prefecture of Xin'an (modern Shexian, Anhui) alone would send 1,500,000 sheets of paper in seven different varieties to the capital at Kaifeng.[22] In 1101, the Emperor Huizong of Song decided to lessen the amount of paper taken in the tribute quota because it was causing detrimental effects and creating heavy burdens on the people of the region.[23] However, the government still needed masses of paper products for the exchange certificates and the state's new issuing of paper money. For the printing of paper money alone, the Song government established several government-run factories in the cities of Huizhou,[which?] Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Anqi.[23]

The workforce employed in these paper money factories was quite large; it was recorded in 1175 that the factory at Hangzhou alone employed more than a thousand workers a day.[23] However, the government issues of paper money were not yet nationwide standards of currency at that point; issues of notes were limited to regional areas of the empire, and were valid for use only in a designated and temporary limit of three years.[17]

Between 1265 and 1274, the late southern Song government introduced a gold- or silver-backed national paper currency standard, which changed the geographic restriction.[17] The range of varying values for these notes was perhaps from one string of cash to one hundred at the most.[17] Ever after 1107, the government printed money in no less than six ink colors and printed notes with intricate designs and sometimes even with mixture of a unique fiber in the paper to combat counterfeiting.

The founder of the Yuan dynasty, Kublai Khan, issued paper money known as Jiaochao. The original notes were restricted by area and duration, as in the Song dynasty, but in the later years, facing massive shortages of specie to fund their rule, the paper money began to be issued without restrictions on duration. The fact that the state was guaranteeing the Chinese paper money impressed Venetian merchants.

Early European paper money

[edit]According to a travelogue of a visit to Prague in 960 by Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, small pieces of cloth were used as a means of trade, with these cloths having a set exchange rate versus silver.[24]

Around 1150, the Knights Templar would issue notes to pilgrims. Pilgrims would deposit valuables with a local Templar preceptory before embarking for the Holy Land and receive a document indicating the value of their deposit. They would then use that document upon arrival in the Holy Land to receive funds from the treasury of equal value.[25][26]

In the 13th century, Chinese paper money of Mongol Yuan became known in Europe through the accounts of travelers, such as Marco Polo and William of Rubruck.[27][28] Marco Polo's account of paper money during the Yuan dynasty is the subject of a chapter of his book, The Travels of Marco Polo, titled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his Country".[29]

All these pieces of paper are, issued with as much solemnity and authority as if they were of pure gold or silver... with these pieces of paper, made as I have described, Kublai Khan causes all payments on his own account to be made; and he makes them to pass current universally over all his kingdoms and provinces and territories, and whithersoever his power and sovereignty extends... and indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan's dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold

In medieval Italy and Flanders, because of the insecurity and impracticality of transporting large sums of cash over long distances, money traders started using promissory notes. In the beginning, these were personally registered, but they soon became a written order to pay the amount to whoever had it in their possession. These notes are seen as a predecessor to banknotes by some but are mainly thought of as proto bills of exchange and cheques.[30] The term "bank note" itself comes from the notes of the bank ("nota di banco") and dates from the 14th century; it originally recognized the right of the holder of the note to collect the precious metal (usually gold or silver) deposited with a banker (via a currency account). In the 14th century, it was used in every part of Europe and in Italian city-state merchants colonies outside of Europe. For international payments, the more efficient and sophisticated bill of exchange ("lettera di cambio"), that is, a promissory note based on a virtual currency account (usually a coin no longer physically existing), was used more often. All physical currencies were physically related to this virtual currency; this instrument also served as credit.

Birth of European banknotes

[edit]

The shift toward the use of these receipts as a means of payment took place in the mid-17th century, as the price revolution, when relatively rapid gold inflation was causing a re-assessment of how money worked. The goldsmith bankers of London began to give out the receipts as payable to the bearer of the document rather than the original depositor. This meant that the note could be used as currency based on the security of the goldsmith, not the account holder of the goldsmith-banker.[32] The bankers also began issuing a greater value of notes than the total value of their physical reserves in the form of loans, on the assumption that they would not have to redeem all of their issued banknotes at the same time. This was a natural extension of debt-based issuance of split tally sticks used for centuries in places like St. Giles Fair,[33] however, done in this way, it was able to directly expand the expansion of the supply of circulating money. As these receipts were increasingly used in the money circulation system, depositors began to ask for multiple receipts to be made out in smaller, fixed denominations for use as money. The receipts soon became a written order to pay the amount to whoever had possession of the note. These notes are credited as the first modern banknotes.[30][34]

The first short-lived attempt at issuing banknotes by a central bank was in 1661 by Stockholms Banco, a predecessor of Sweden's central bank, Sveriges Riksbank.[18] These replaced the copper-plates being used instead as a means of payment.[35] The peculiar circumstances of the Swedish coin supply were what led to this banknote issue. Cheap foreign imports of copper had forced the Crown to steadily increase the size of the copper coinage to maintain its value relative to silver. The heavy weight of the new coins encouraged merchants to deposit it in exchange for receipts. These became banknotes when the manager of the bank decoupled the rate of note issue from the bank currency reserves. Three years later, the bank went bankrupt after rapidly increasing the artificial money supply through the large-scale printing of paper money. A new bank, the Riksens Ständers Bank, was established in 1668, but did not issue banknotes until the 19th century.[36]

Permanent issue of banknotes

[edit]

The idea that social and legal consensus determines what constitutes money is the foundation of modern banknotes. A gold coin's value is simply a reflection of the supply and demand mechanism of a society exchanging goods in a free market, as opposed to stemming from any intrinsic property of the metal. By the late 17th century, this new conceptual outlook helped to stimulate the issue of banknotes. The economist Nicholas Barbon wrote that money "was an imaginary value made by a law for the convenience of exchange".[37]

A temporary experiment of banknote issue was carried out by Sir William Phips as the governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay starting on December 20, 1690,[38] to help fund the war effort against France.[39] The other Thirteen Colonies followed in Massachusetts' wake and began issuing bills of credit, an early form of paper currency distinct from banknotes, to fund military expenditures and for use as a common medium of exchange.[40] By the 1760s, these bills of credit were used in the majority of transactions in the Thirteen Colonies.[41]

The first bank to initiate the permanent issue of banknotes was the Bank of England. Established in 1694 to raise money for the funding of the war against France, the bank began issuing notes in 1695 with the promise to pay the bearer the value of the note on demand. They were initially handwritten to a precise amount and issued on deposit or as a loan. There was a gradual move toward the issuance of fixed denomination notes, and by 1745, standardized printed notes ranging from £20 to £1,000 were being printed. Fully printed notes that did not require the name of the payee and the cashier's signature first appeared in 1855.[42]

The Bank of Scotland was established in 1695 to support Scottish businesses, and in 1696 became the first European bank to issue banknotes in fixed values. It continues to issue banknotes and is the longest continuous banknote issue in the world.[43]

The Scottish economist John Law helped establish banknotes as a formal currency in France, after the wars waged by Louis XIV left the country with a shortage of precious metals for coinage.[contradictory][citation needed]

In the United States, there were early attempts at establishing a central bank in 1791 and 1816, but it was only in 1862 that the federal government of the United States, began to print banknotes.[citation needed]

Central bank issuance of legal tender

[edit]The examples and perspective in this deal primarily with the United Kingdom and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2025) |

Originally, the banknote was simply a promise to the bearer that they could redeem it for its value in specie, but in 1833, the second in a series of Bank Charter Acts established that banknotes would be considered as legal tender during peacetime.[44]

Until the mid-nineteenth century, commercial banks were able to issue their own banknotes, and notes issued by provincial banking companies were the common form of currency throughout England, outside London.[45] The Bank Charter Act of 1844, which established the modern central bank,[46] restricted authorisation to issue new banknotes to the Bank of England, which would henceforth have sole control of the money supply in 1921. At the same time, the Bank of England was restricted to issue new banknotes only if they were 100% backed by gold or up to £14 million in government debt. The Act gave the Bank of England an effective monopoly over the note issue from 1928.[47][48]

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]

Prior to the introduction of paper money, precious or semiprecious metals minted into coins to certify their substance were widely used as a medium of exchange. The value that people attributed to coins was originally based upon the value of the metal unless they were token issues or had been debased. When paper money was issued by banks, that was originally a claim for the coins held by the bank, but due to the ease with which they could be transferred and the confidence that people had in the capacity of the bank to settle the notes in coin if presented, they became a popular means of exchange in their own right. They now make up a very small proportion of the "money" that people think that they have, as demand deposit bank accounts and electronic payments have negated much of the need to carry notes and coins.

Paper money has a natural advantage over coins in that it is lighter to carry; but it is also less durable than coins. Banknotes issued by commercial banks had counterparty risk, meaning that the bank may not be able to make payment when the note was presented. Notes issued by central banks had a theoretical risk when they were backed by gold and silver. Both notes and coins are subject to inflation. The durability of coins means that even if metal coins melt in a fire or are submerged under the sea for hundreds of years, they still have some value when they are recovered. Gold coins salvaged from shipwrecks retain almost all of their original appearance, but silver coins slowly corrode.[49][50]

Other costs of using bearer money include:

- Discounting to face value: Before national currencies and efficient clearing houses, banknotes were only redeemable at face value at the issuing bank. Even a branch bank could discount notes of other branches of the same bank. The discounts usually increased with distance from the issuing bank. The discount also depended on the perceived safety of the bank. When banks failed, the notes were usually partly redeemed out of reserves, but they sometimes became worthless.[51][52] The problem of discounting within a country does not exist with national currencies.

- Counterfeiting paper notes has always been a problem, especially since the introduction of color photocopiers and computer image scanners. Numerous banks and nations have incorporated many types of countermeasures in order to keep the money secure. However, extremely sophisticated counterfeit notes known as superdollars have been detected in recent years.

- Manufacturing or issue costs. Coins are produced by industrial manufacturing methods that process the precious, semi-precious, or other metals, and require additions of alloy for hardness and wear resistance. By contrast, bank notes are printed paper (or polymer), and typically have a higher cost of issue, especially in larger denominations, compared with coins of the same value.[dubious – discuss]

- Wear costs. Banknotes do not lose economic value by wear, since, even if they are in poor condition, they are still a legally valid claim on the issuing bank. However, banks of issue do have to pay the cost of replacing banknotes in poor condition, and paper and even polymer notes wear out much faster than coins.

- Cost of transport. Coins can be expensive to transport for high value transactions, but banknotes can be issued in large denominations that are much lighter than the equivalent value in coins.

- Cost of acceptance. Coins can be checked for authenticity by weighing and other forms of examination and testing. These costs can be significant, but good quality coin design and manufacturing can help reduce these costs. Banknotes also have an acceptance cost – the expense of checking the banknote's security features and confirming acceptability of the issuing bank.

The different advantages and disadvantages of commodity money and paper money imply that there may be an ongoing role for both forms of bearer money, each being used where its advantages outweigh its disadvantages.

Paper money collecting as a hobby

[edit]Paper money collecting, also referred to as banknote collecting or notaphily, is a slowly growing area of numismatics. Although generally not as widespread as coin and stamp collecting, the hobby is slowly expanding. Prior to the 1990s, currency collecting was a relatively small adjunct to coin collecting, but currency auctions and greater public awareness of paper money have caused more interest in rare items and consequently their increased value.[citation needed] The most valuable note is the $1000 bill issued in 1890 that was sold at an auction for $2,255,000.[citation needed]

Trades

[edit]For years, the mode of collecting paper money was through a handful of mail order dealers who issued price lists and catalogs. In the early 1990s, it became more common for rare notes to be sold at various coin and currency shows via auction. The illustrated catalogs and "event nature" of the auction practice seemed to fuel a sharp rise in overall awareness of paper money in the numismatic community. The emergence of currency third party grading services (similar to services that grade and "slab", or encapsulate, coins) also may have increased collector and investor interest in notes. Entire advanced collections are often sold at one time, and to this day, single auctions can generate millions in gross sales. Today, eBay has surpassed auctions in terms of the highest volume of sales of banknotes.[53][54][55] However, rare banknotes still sell for much less than comparable rare coins. This disparity is diminishing as paper money prices continue to rise. A few rare and historical banknotes have sold for more than a million dollars.[56]

There are many different organizations and societies around the world for the hobby, including the International Bank Note Society (IBNS), which currently asserts to have around 2,000 members in 90 countries.[57]

Novelty

[edit]The universal appeal and instant recognition of paper money have resulted in a plethora of novelty merchandise that is designed to have the appearance of paper currency. These items cover nearly every class of product. Cloth material printed with banknote patterns is used for clothing, bed linens, curtains, upholstery, and more. Acrylic paperweights and even toilet seats with bank notes embedded inside are also common. Items that resemble stacks of bank notes and can be used as a seat or ottoman are also available.

Manufacturers of these items must take into consideration when creating these products whether the product could be construed as counterfeiting. Overlapping note images and/or changing the dimensions of the reproduction to be at least 50% smaller or 50% larger than the original are some ways to avoid the risk of being considered a counterfeit. But in cases where realism is the goal, other steps may be necessary. For example, in the stack of banknotes seat mentioned earlier, the decal used to create the product would be considered counterfeit. However, once the decal has been affixed to the resin stack shell and cannot be peeled off, the final product is no longer at risk of being classified as counterfeit, even though the resulting appearance is realistic.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "paper money". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ "banknote". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ "Legal Tender Guidelines". British Royal Mint. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ^ Hammurabi (1903). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Records of the Past. 2 (3). Translated by Sommer, Otto. Washington, DC: Records of the Past Exploration Society: 75. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

100. Anyone borrowing money shall ... his contract [for payment].

- ^ Hammurabi (1904). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon" (PDF). Liberty Fund. Translated by Harper, Robert Francis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

§100. ...he shall write down ... returns to his merchant.

- ^ a b Hammurabi (1910). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Avalon Project. Translated by King, Leonard William. New Haven, CT: Yale Law School. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Hammurabi (1903). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Records of the Past. 2 (3). Translated by Sommer, Otto. Washington, DC: Records of the Past Exploration Society: 77. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

122. If anyone entrusts to ... have committed an offence.

- ^ Hammurabi (1904). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon" (PDF). Liberty Fund. Translated by Harper, Robert Francis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

§122. If a man give ... it from the thief.

- ^ Jones, John Percival (1890). Speeches of J.P. Jones: Money and Tariff, 1890–93. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Moulton, Luther Vanhorn (1880). The Science of Money and American Finances. Co-operative Press. p. 134.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1921). The outline of history, being a plain history of life and mankind. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ "The History of Money". pbs.org – Nova. 26 October 1996. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Ancient Roman IOUs Found Beneath Bloomberg's New London HQ". 2016-06-01. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ^ Allen, Tony; Grant, R. G.; Parker, Philip; Celtel, Kay; Kramer, Ann; Weeks, Marcus (2022). Timelines of World History. New York: DK. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7440-5627-3.

- ^ a b c d Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), p. 156.

- ^ a b Bowman (2000), p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f Gernet (1962), p. 80.

- ^ a b Geisst, Charles R. (2005). Encyclopedia of American business history. New York. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8160-4350-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Chapter 12: Security Printing and Seals" (PDF). Security Engineering: A Guide to Building Dependable Distributed Systems. p. 245. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

The introduction of paper money into Europe by Napoleon in the early 1800s, and of other valuable documents such as bearer securities and passports, kicked off a battle between security printers and counterfeiters

- ^ Peter Bernholz (2003). Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-84376-155-6.

- ^ Daniel R. Headrick (2009). Technology: A World History. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-988759-0.

- ^ Needham (1986), p. 47.

- ^ a b c Needham (1986), p. 48.

- ^ Jankowiak, Marek. Dirhams for slaves. Medieval Seminar, All Souls, 2012, p. 8

- ^ Sarnowsky, Jürgen (2011). Templar Order. doi:10.1163/1877-5888_rpp_com_125078. ISBN 978-9-0041-4666-2.

- ^ Martin, Sean (2004). The Knights Templar: The History and Myths of the Legendary Military Order. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1560256458. OCLC 57175151.

- ^ William N. Goetzmann; K. Geert Rouwenhorst (2005). The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-19-517571-4.

The Mongols adopted the Jin and Song practice of issuing paper money, and the earliest European account of paper money is the detailed description given by Marco Polo, who claimed to have served at the court of the Yuan dynasty rulers.

- ^ Moshenskyi, Sergii (2008). History of the weksel: Bill of exchange and promissory note. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4363-0694-2.

- ^ Marco Polo (1818). The Travels of Marco Polo, a Venetian, in the Thirteenth Century: Being a Description, by that Early Traveller, of Remarkable Places and Things, in the Eastern Parts of the World. pp. 353–355. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ^ a b De Geschiedenis van het Geld (the History of Money), 1992, Teleac, p. 96

- ^ "Sverige, Palmstruchska banken, Kreditsedel 10 daler silvermynt, 17 april 1666" [Europe's first banknotes]. Alvin (in Swedish).

- ^ Faure AP (6 April 2013). "Money Creation: Genesis 2: Goldsmith-Bankers and Bank Notes". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2244977.

- ^ Tymoigne, Eric; Wray, L. Randall (July 2005), Money: An Alternative Story, doi:10.2139/ssrn.1009611, S2CID 2254888, SSRN 1009611, archived from the original on 20 September 2022, retrieved 1 September 2022

- ^ Vincent Lannoye (2011). The History of Money for Understanding Economics. Vincent Lannoye. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4802-0066-1. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Karl Gunnar Persson (2010). An Economic History of Europe: Knowledge, Institutions and Growth, 600 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0521549400. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ "The first European banknote". Cité de l’économie et de la monnaie. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Nicholas Barbon, Discourse on Trade, 1690. p. 37

- ^ Andrew McFarland Davis, Currency and Banking in the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay, Volume 1, Issue 4 (American Economic Association, 1900) p.10

- ^ Patrick Dillon (2007). The Last Revolution: 1688 and the Creation of the Modern World. Random House. pp. 344–346. ISBN 978-1844134083.

- ^ Newman, Eric P. (1990). The Early Paper Money of America (3rd ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-120-X.

- ^ Bouton, Terry (2007). Taming Democracy: "The People," the Founders, and the Troubled Ending of the American Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0195378566. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "A brief history of banknotes". Bank of England. Archived from the original on 2013-09-29. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ^ "The history of Bank of Scotland". Lloyds Banking Group. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Currency and Bank Notes Act, 1928" (PDF). www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ "£2 note issued by Evans, Jones, Davies & Co". British Museum. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Capie, Forrest; Fischer, Stanley; Goodhart, Charles; Schnadt, Norbert (1994). "The development of central banking". The future of central banking: the tercentenary symposium of the Bank of England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5214-9634-6. Retrieved 2012-12-17 – via LSE Research Online.

- ^ Jeffrey A. Tucker (16 September 2010). "Yesterday was a Historic Day". Mises Wire. Mises Institute. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ Horsefield, J. K. (Nov 1944). "The Origins of the Bank Charter Act, 1844". Economica. New. 11 (44): 180–189. doi:10.2307/2549352. JSTOR 2549352.

- ^ Famous shipwrecks from which valuable precious metals and coins were recovered in recent years include the Atocha and the SS Central America. Shipwreck coins are highly collectible, and dealers sometimes post photos on the internet.

- ^ "Virtual Shipwreck and Hoard Map by Daniel Frank Sedwick, LLC". sedwickcoins.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Atack & Passell (1994), pp. 84–86.

- ^ Taylor, George Rogers (1951). The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. New York, Toronto: Rinehart & Co. ISBN 978-0-87332-101-3.

- ^ "You Won a Lottery, Got an Award, or a Mystery Shopper Job and They Sent You a Check! Counterfeit Cashiers Checks". Consumer Fraud Report. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ "Forged German Treasure Banknotes". mebanknotes. 28 May 2008. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ Cyndy Aleo-Carreira (25 March 2009). "2 Million Counterfeit Items Removed From EBay". PC World. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ Bank Note (23 August 2011). "Long Beach Sale Set". World Record Academy. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ "Introducing the IBNS". IBNS. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

Bibliography

[edit]- Atack, Jeremy; Passell, Peter (1994). A New Economic View of American History. New York: W.W. Norton and Co. ISBN 978-0-393-96315-1.

- Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-2311-1004-4.

- Ebrey; Walthall; Palais (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-6181-3384-0.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0720-6.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5218-7566-0.

- Mockford, Jack (2014). "They are Exactly as Banknotes are": Perceptions and Technologies of Bank Note Forgery During the Bank Restriction Period, 1797–1821 (PDF) (PhD). University of Hertfordshire.